The Process is the Project

Article - April 8, 2014

The furniture-making process is one that I think about a lot, though admittedly my mind is mostly focused on the actual cutting of wood and the tools required to do the work. As I recently discovered, the construction of a piece of furniture is only one slice of a delicious and much larger pie. I guess I always knew that the earlier parts of the process (those surrounding design) were both challenging and rewarding, but it wasn’t until I completed the Blacker House Chair recently that things became so painfully obvious to me. More on the chair later.

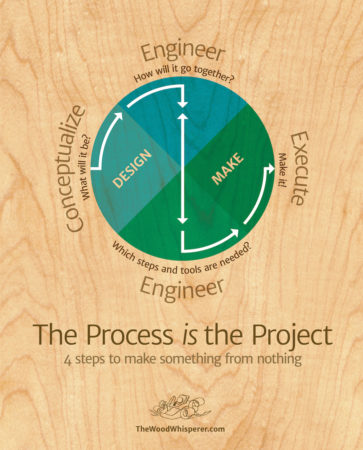

So let’s start this bit of public self-reflection by laying out the four phases of the creation process, as I see them. Although my focus here is on furniture, I believe these phases apply to any creative project be it physical, digital, edible or audible.

1- Conceptualize the design

2- Engineer the design

3- Engineer the build

4- Execute the build

We now have posters of this infographic available for purchase!

The Four Phases

Phase One – Conceptualize the Design

In the simplest terms this phase answers the questions, “What will it be? What does it do? What does it look like?” In other words, it’s all about developing the form and function. For a guy like me, the visual aspect of a piece of furniture is the most challenging. Fortunately, most functional pieces will naturally limit our visual options to some extent; and that does help. But I personally find it very difficult to create something out of nothing and most of my designs are largely derivative of other objects I’ve seen in my life. Some might argue that all designs are derivative these days, but I think more than a few lucky people simply have a knack of coming up with designs that are different enough to be considered unique. I am not one of those people.

Phase Two – Engineer the Design

Once you know what you want this thing to look like, you have to engineer the joinery and other elements that will hold it together. If the first phase declares, “Part A connects to Part B at a 30 degree angle.” the second phase must ask, “How will Part A connect to Part B?” So the real value in this phase is that it ensures whatever is being made will not only work, but will not fall apart after its first use.

Phase Three – Engineer the Build

After we have a form and the structural elements to support it we have to decide what tools and jigs we’ll need to create the various parts. If the previous phase says, “Here are the joints you need to cut.” Phase 3 asks “How should I cut them?” This is actually much harder than it sounds and creativity and experience will go a long way. I often say that woodworking is nothing but a series of steps. Some people know the steps and some don’t. Once you know that series of steps, you too can make that particular piece. The sometimes seemingly “magical” series of steps is the stuff that makes up this phase. Some questions you’ll have to answer are: “In what order will I construct the parts? What tools will I use? How will I use those tools? What jigs might I employ to make the process accurate and repeatable?”

What’s cool about this particular phase is that it can often lead you backwards. Let’s say the part required to achieve a desired curve is just too severe and the material repeatedly breaks. If there’s no feasible way to create the part, it’s time to take a step back and revisit the design. Perhaps a slight modification in the design will yield a part that can be created with the tools, materials, and skills we currently have access to.

Phase Four – Execute the Build

While the three previous phases fall under the umbrella of thinking, the last phase is all about doing. A skilled set of hands is required to bring the project to life. This is where the craftsmanship comes into play. Music provides an apt metaphor. Just because someone can play a piece of sheet music perfectly doesn’t mean they can play it in a way that touches the listener’s emotions as the original composer intended. Subtle elements brought to the music by the player have the potential to fill the gaps between the notes, giving the piece a sense of drama and purpose. This is what a good woodworker can do with a simple set of plans; creating a piece to specification while leaving their own echo of personality and style.

Each phase is as challenging as it is necessary. If you leave anything out, the entire project could fall apart. A brilliant design amounts to very little if there isn’t someone there to craft it into existence. A terrible design is still terrible even if it’s built by a seasoned craftsperson.

Do You Need to Master All Phases?

Does success hinge upon a single person mastering all aspects of the creative process? Absolutely not. Look no further than your average large company for an example of efficient (sometimes?) specialization. In other words, they let the designers design and the builders build. Even Greene & Greene furniture (a woodworker favorite) was designed by the Greene brothers and built by the Hall brothers. Obviously, the system becomes much more efficient when the specialist of a particular phase has a knowledge-base that extends into the other phases as well. So as an individual, you are in an excellent position to design remarkable objects thanks to your knowledge and understanding of the tools and techniques used to bring it to life. There’s no better way for the left hand to know what the right hand is doing than to have those hands attached to the same body.

So while it might be nice to daydream about having a design passed down to your shop from the Creative Department, the truth is you are most likely at your happiest when you have a hand in all four phases (at least I am). Of course there are always exceptions and plenty of talented woodworkers are perfectly content building everything from pre-defined plans. But for most people, I have to imagine your enjoyment of the process goes beyond just building. For better or for worse, I will continue to dabble in all phases of the process.

The Blacker House Chair

The genesis for this conversation was my recent Blacker House Chair class at the William Ng School. I have adored the design of this chair for years now and in many ways, I consider it to be one of the most interesting pieces of furniture ever built. And now I own one that was made with my own two hands. You might think I’d be overwhelmed by the sense of accomplishment having reached a pinnacle of my building career, but the truth is I’m not. Don’t get me wrong, I feel incredibly satisfied with the experience and I learned a LOT. In fact, I think I learned more during this chair build than I have on any previous project. But something’s definitely missing. It wasn’t until I sat down (in my new chair) to ponder my feelings on the situation that I figured it out: the Blacker House Chair experience consisted of only one single phase of the process.

The genesis for this conversation was my recent Blacker House Chair class at the William Ng School. I have adored the design of this chair for years now and in many ways, I consider it to be one of the most interesting pieces of furniture ever built. And now I own one that was made with my own two hands. You might think I’d be overwhelmed by the sense of accomplishment having reached a pinnacle of my building career, but the truth is I’m not. Don’t get me wrong, I feel incredibly satisfied with the experience and I learned a LOT. In fact, I think I learned more during this chair build than I have on any previous project. But something’s definitely missing. It wasn’t until I sat down (in my new chair) to ponder my feelings on the situation that I figured it out: the Blacker House Chair experience consisted of only one single phase of the process.

I didn’t conceptualize this chair. Charles Greene did. I didn’t engineer the joinery. Again, Charles Greene did. I didn’t even engineer the building process as that credit goes to William Ng. All I had to do was take the raw materials and shape them according to William’s process and Charles Greene’s design. As someone who aspires to have a hand in all phases of furniture-making, you might now see how coming home with a complete Blacker House Chair after an 8-day class might not hold the same level of accomplishment and personal satisfaction as executing a much simpler design that was one of my own creation.

I don’t think I’ll ever be able to design something as complex and unique as the Blacker House Chair, but building one certainly opened my eyes to new design possibilities. Seeing how William tackled the various construction challenges helped me realize that just about any joint or shape can be made with enough forethought (and tools). And that’s why I wouldn’t hesitate to take a class like this again in the future. While it’s true that my only job was to build the chair, I walked away with a greater understanding of the Blacker House Chair design and the logic behind its construction. These are things I could very well apply to other projects in the future when I am in complete control of all phases of the process.

I can’t really claim to have any real moral to this story. I’m really just thinking out loud and sharing my understanding of my personal situation with you. Perhaps this will get your gears turning and help you identify which parts of the process you’re weak in and how you might go about improving them. Now that I have worked this out in my head, I feel I have a much better understanding of who I am as a woodworker and what my goals should be. Just a little food for thought. And now I’m full.

What About You?

How do you view your role in the furniture-building process? Do you typically spend most of your time in one phase or another? Is there a phase you excel at or one that you avoid at all costs? I’m curious to hear your feedback.